I'll admit that this choice was a true shot in the dark. Normally I would spend hours online looking for films from a certain country and upon finding potential selections spend additional time researching their production details in order to confirm that they satisfy my inclusion criteria. However in late summer of 2020 I was finally able to enter public libraries again and on one such visit had a passing thought to browse the international film DVDs in order to find a selection for Iran. Browsing through the titles for both the ‘Persian’ and “Farsi’ sections I came across Majid Majidi’s Baran. It wasn’t until I took this DVD home when I conducted my research and realized that I could potentially critique the film for this series. I mean I would have watched the film anyway.

As for its’ economic foray into America, Miramax secured the distribution rights and gave the film a couple of runs in a limited number of theaters between the fall of 2001 and the following spring. Disney, which owned Miramax at the time, released the film on DVD in October of 2002 through its Buena Vista Home Entertainment division. The copies of such distribution have been well maintained at American libraries. Based on the information at worldcat.org, there were 5 public libraries within a 20 mile radius of where I live that held a copy. Within a 40 mile radius the number of libraries goes up to 17. Overall I’d say that there’s roughly 400 holdings in the US alone. The film is also available for rental at Facets, and can be streamed online at Amazon, Vudu, YouTube and other sites for those of you who still cling to the stubbornly irrational notion that you should spend your hard earned money to watch films.

The first thing that really caught my eye in this film was its cinematography. The camerawork was exceptional, especially with the graceful way the filmmakers integrated motion into their shots. An early sequence that I found rather remarkable was the establishing shot of Soltan and Rahmat as they arrived at the construction site. The camera continuously followed them as they entered the site and climbed two stories to talk to Memar. I was quite impressed with the skill and talent that it took to pull off a lengthy 90 second take that included multiple vertical and horizontal pans and which effortlessly maintained its focus on the two characters of interest. The timing of the camera movement in step with the pace of the performers as they made their way through the site was impeccable. This early dose of quality really pulled me into the film, as it indicated a high level of expertise and dedication to the craft from the filmmakers.

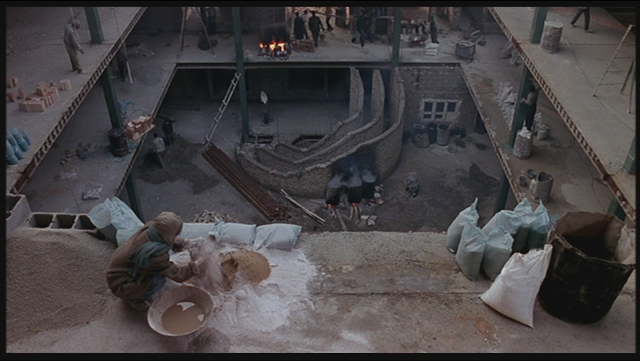

But once you get past the technical brilliance of this sequence it still worked magnificently as an establishing shot in order to set the stage for the environment in which these workers spent their days. Everything about the building site had a strong motif of dirt, dust, grime and smoke. It provided the perfect visual representation for the despair and hardships that these workers were going through. In addition to this the stark imagery of the winter scenes in the middle of the film had a dire, haunting, and foreboding feel to them which contributed to the cold muted tone of the film. Generally I regarded the mise-en-scène throughout the film to be quite exceptional.

Even beyond the use of motion, the framing of the shots were absolutely pitch perfect at times. For instance in one scene Lateef would climb the stairs with the camera stopping to catch a perfect vantage point of the construction workers as seen through an entryway. There was also an interesting shot of Rahmat sitting on the stairs after spilling a bag of plaster, not to mention the numerous shots that looked down into the opening in the middle of the building. If this wasn’t enough the shot of the workers in the river framed under an archway of a bridge was a great example of how artfully staged the shots in this film were.

I also thought highly of the editing and pace of the film even during the weaker moments in the narrative. From a purely cinematographic perspective, this was one of the best films that I’ve ever seen. The high quality of this work was also notably achieved without any indulgence in stylish flair or unnecessary exuberance. There was a certain subtle, sublime quality to its unassailable artistic merit. In its rather austere understated approach it left some room for the acting to have a modest impact on the film.

As for the acting I found the film to exhibit an intriguing concept whereby the qualitative aspect of all the performances were indicative of the character’s relative comfort with their current social situation in life. The inspectors for instance conducted their business in a straightforward no-nonsense manner that exuded a certain suave and impeachable confidence. When in the presence of the inspectors or even the engineers, Mohammad Amir Naji played Memar as a man with a decent level of apprehension and self-doubt. When not in the presence of either Amir Naji allowed Memar’s true personality to shine. Memar was seen as forceful, brute, and yet full of boisterous verve. He ran the building site with a very stern, fervent hand that generated a modicum of both respect and fear from his employees. At times Amir Naji gave a very commanding performance that really stood out among the rest of the cast. But what was truly great about Amir Naji’s performance was that he played the character with just enough warmth and humanity that one didn’t truly think of him as a villain. The fact that he could be swayed by Lateef’s emotional pleas made him more complex and intriguing as a character who’s constantly torn between caring for the welfare of his workers and ensuring that the job gets done.

As one proceeded downward through the workplace hierarchy the characters were portrayed with decreasing levels of self-confidence and stability. Hossein Abedini set the tone for Lateef early in the film as a childish, mischievous character who was gregarious enough to take pleasure in the silly playfulness of others. Abedini also deftly expressed his character’s immaturity and inability at handling the complications that life threw at him. Through Abedini’s performance one sees a character who was a bit too brash and eager for trouble, and yet beset by confusion and insecurity in dealing with the emotions that he felt after discovering Baran. I thought Abedini did a great job in regards to the latter. The only part of Abedini’s performance that I despised were the emotional pleas that he made towards Memar. Here Lateef seemed too guileful and desperate in his desires to be truly believed, especially to someone with the intelligence of Memar. Granted in fairness to Abedini, Lateef’s reasons were forged even within the context of the film’s narrative, so this can be excused ever so slightly.

The Afghan characters in the film were primarily noted for the precarious nature of their existence within this world. While Abbas Rahimi didn’t get a lot of screen time, one of the more indelible moments in the film was his subtle physical reaction as Solton after Memar curtly suggested that he could be fired from his job. The resulting image of Soltan was of a character so powerless that he was practically paralyzed into a catatonic state of fear over losing any source of income, no matter how meager it was. Even if Rahimi’s overall impact on the film was rather small, his performance in this one scene was excellent. Of course there were even greater difficulties for Rahmat, as played by Zahra Bahrami. In having to conceal both her gender and her national identity, Bahrami beautifully played a character who was so submissive and docile that she was rendered completely mute.

The fact that the movie was named after a character who never uttered a single word easily established the notion that this was not a dialogue heavy picture. A lot of the communication that existed between the characters was done with silent, furtive glances. Here I found Bahrami’s work to be especially good given how much personality that she injected into the role. I liked the fear that she expressed when being spotted by the inspectors, the subtle half-smile that she gave to Lateef when seeing him for the last time, as well as her visage of general shock and apprehension when seeing Lateef at the shrine. Abedini similarly did good work in this regard as well, and generally I find that this type of acting tends to be more culturally transcendent, given its greater focus on basic human emotions. I got the impression that for someone who doesn’t speak the language of the characters in the film, they could turn the subtitles off and not really miss that much in regards to the exposition for the story.

Granted with or without subtitles, the film’s narrative would still be its weakest element. It started out with a rather intriguing premise given the scheme that Rahmat attempted to pull off in order to generate some income for her family. At the very least this offered two important plot points, one being Lateef’s discovery of Rahmat’s personal secret, which drastically altered the relationship between the two characters and the other being Rahmat’s exposure to the inspectors which provided for the film its lone source of dramatic action. The problem with the narrative was that once the Afghans at the construction site got exposed, the story had nowhere to go and simply clung to the tenuous thread that existed between Lateef and Baran.

I must admit that there was also a part of me that was annoyed by Lateef’s awkward timidness in approaching Baran. While such qualities were appropriately consistent with how Abedinin portrayed the character, it largely left the latter half of the film stuck in neutral with little forward momentum. I craved the progression that could only be achieved if the two were able to meet again. Perhaps though, I have to ponder if the film’s intent was to establish thematically that such a notion was tragically unfeasible. There really was no suspense in delaying the inevitable here since any relationship between the two characters was doomed from the beginning. Furthermore, any payoff in such a meeting would ultimately prove to be disappointing. Lateef’s romantic advances weren’t just unrequited, they were downright quixotic.

This aspect in particular though did make me question the purpose of the film. If one wanted to chronicle the plight of Afghan refugees, then why establish a legal resident like Lateef as the protagonist for a story that then is told from his perspective? Any attempt to show that these people were at the mercy of those around them, becomes incredibly difficult when done through the prism of someone who actually possessed such mercy and was willing to perform irrational acts based on it. Ultimately though the inadequacies in the narrative and its focus on Lateef’s romantic entanglement didn’t detract too much from the high production quality seen elsewhere. This was an excellent film, and I’m happy that fate intervened in this case.